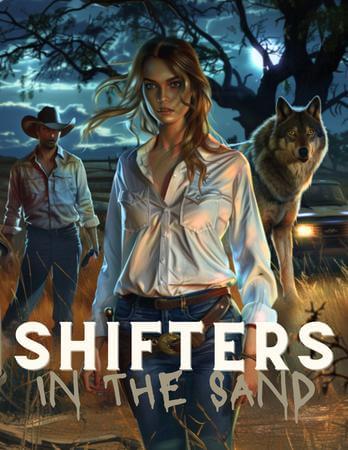

Shifters in the Sand

Isabelle is an ambitious photojournalist who's tired of getting passed over for real news stories that always seemed to go to her male colleagues. When her boss sends her to New Mexico to do yet another puff piece, she can't help but wonder if it has less to do with her gender and more to do with her personally. She arrives at a secluded ranch run by Cormac, a handsome and not-so-inviting rancher, and his housekeeper and friend Tara, an older woman who knows more than she lets on. At first, the assignment and everyone at the ranch appears to be on the level but one night Isabelle catches a glimpse of a creature she's never seen before. A creature that looks to be half man, half wolf... Soon Isabelle finds herself plunged into a hidden world whose inhabitants the Shifters will do anything to keep their secret, and is stuck in a power struggle she hardly understands. Can she trust Cormac, a man she can't help but be drawn to, or is he trying just as hard as the rest of them to keep her quiet? And can Cormac, torn between attraction and loyalty, help Isabelle uncover the answers about who is trying to expose the shifters to everyone?

Tags:

Word Count: 92,530

Rating: 4.7

Likes: 0

Status: Completed

Chapter 1: Isabelle

Word Count: 2,533

There was nothing in the desert, and that’s what Isabelle liked about it. Everywhere she ever lived from childhood onward was packed with things: trees and houses and mountains and stimuli bombarding each inch her eye framed. In the desert, she felt like she could see forever; that the edge of the world was just there beyond the horizon, and she could find it and could touch it, and plunge over the side of it if she wanted to.

In the cluttered office she shared with two other journalists, tucked in the midst of downtown Denver, she stared out the window as she packed the last of her equipment, counting the turrets of mountains that framed the view like a crown. She was being sent on assignment, told little beyond the fact that “they” needed shots of a ranch and b-roll of the desert, and “they” were sending her via train because it was too last minute to buy a ticket for a flight or more accurately, too expensive at the last minute. “They” were always doing things like that to her.

“They sure are cheap bastards, huh?” her officemate Terry said as he watched Isabelle gingerly place the last of her lenses into the padded case with the concern usually reserved for parents putting their children into bed. “Ya know, they flew Shapiro to Seattle pretty recently, and it was way more last minute than this assignment.”

“I like the train anyway,” Isabelle told him even though she was only half listening. At that point, she was on autopilot. She just knew Terry well enough that she knew he was trying to get her to complain. Complaining was the unspoken privilege of men in her world, whereas she had to walk on eggshells and shrug off indignities the rest of them would never endure.

“You’re such a trooper.”

Terry put his feet up on his desk, knocking several papers down as he did. Most of the office was a mess, and Isabelle was as guilty as the rest of them. She surveyed her own space, noting the collection of paper coffee cups gathering in the corner where she had herded them with every intention of eventually throwing them out. There was so much everywhere, cups and crinkled pieces of note paper and pens rolling freely across formica surfaces as if pushed along by a fidgety phantom hand. Isabelle found herself suddenly craving the wide open spaces she was about to visit; the visible, tangible horizon.

Isabelle snapped closed the latch on her equipment carrier, trying not to stare at the dirty, worn soles of Terry’s shoes. “Well, I like traveling anyway so I don’t mind the longer trip. Besides-” she blinked out the window at the close clutter of the city, densely packed together- “I need a change of scenery.”

“You say that now but after a week in the desert, you’ll be thrilled to be back here.”

“Wanna know my favorite thing about you, Terry?” Isabelle asked, still avoiding a glimpse at his dirty shoes snowing flecks of street residue on his desk. “You always seem to know exactly how I’m going to feel about things.”

Terry dropped his feet to the floor, coming to an upright but hunched over the desk position. Isabelle was aware of how he was trying to make his face mean when he spoke to her, and she allowed herself a moment of pity for his attempted scowl reaching for an emotion much larger and more experienced than he was.

“Don’t run your mouth too much down there in New Mexico,” he told her.

Isabelle swung her bag over her shoulder, one arm hanging loose at her side and the other propped on her hip. Theirs was an uneasy truce of a relationship, a parallel existence forced into being by lack of office space in the creaky stone and wood building. It didn’t matter who it was in there with her; as a general rule, Isabelle always felt like she didn’t have enough room.

And it could have been worse, which is cold comfort but the truth. Even some of the other men who worked on news production with her treated her worse than Terry. Terry at least came at her from an even playing field, let their dynamic play out as spars and verbal jabs. The other men spoke to her like a child who didn’t understand what she was being asked to do. To her face, they were condescending. Behind her back, they were vulgar.

“We’ll miss you, Isabelle,” Terry said as he watched her propped the door open with her hip to lug the last of her equipment out of the office. “It’s going to be such a sausage fest without your estrogen softening up the place.”

Isabelle gifted him with a bitter smile. “Thanks, Terry. Don’t be afraid to try cutting off your oxygen when you jerk it tonight. With any luck, it’ll kill ya.”

“Sugar and spice and everything nice,” Terry chanted as the door swung shut behind her, muffling him slightly but not enough to block him out.

The cab she had called for was idling downstairs in front of the building, the driver staring into space as she approached.

“You’re the lady I’m picking up, right?” he asked, rolling down the passenger side window.

“That’s right.”

“Ya don’t need any help with that junk?” he asked as Isabelle lifted a heavy looking black case and lowered it cautiously into the back of the car.

“Don’t worry about it,” Isabelle said as she closed the trunk.

The cab driver wasn’t much for small talk, which was exactly how Isabelle wanted it. She felt like she was always talking, always explaining or arguing or lamenting or begging permission to get one last shot, ask one more question, try one more location. Silence was a rare commodity in her life. Space and silence and nobody mentioning how odd it was that she was the only woman in the room.

Isabelle rested her head against the vinyl seat, creased and bleeding tufts of white fuzz like fat leaking from a slice in living flesh. She pressed her fingers into the spindly material, watched it break apart as she applied pressure, cotton candy and cumulus clouds.

“Going somewhere for the TV station?” the driver asked.

“Heading to New Mexico for some footage of ranches and deserts. Maybe a few interviews with the people who still own them. It’s not a world many of us are familiar with.”

The vehicle came to a rickety halt, and the cab driver turned around as he flipped the meter off. Isabelle held out a twenty, waited for him to ask her how much change she wanted back. Instead, the driver just kept looking at her.

“You can just give me five back,” Isabelle said after a long enough pause.

“They’re gonna love you down there.” The driver finally broke out of his trance and took Isabelle’s money. “The cowboys, I mean.” He handed her back a five. “You’re their kind of woman.”

“You don’t say.”

“Cowboys are a different breed. They don’t like a woman that’s too, what’s the word? Flimsy.”

“Well, I’m certainly not that.”

Isabelle moved faster out of the cab than she had to but she was tired of this game, even if it wasn’t played for a sexual reason, for a lecherous reason. Men expected her to talk to them and absorb their compliments; being flattered and taken by how they noticed something special in her. The only problem was that Isabelle had spent most of her life in the company of men, and realized very early on how they all had the same scripts, used the same phrases and lines; aimed for the same targets and wanted the same goals. By the time she was a slightly too tall fourteen year old, she was well aware of what flattery meant to men, and how specifically she was expected to react to it.

At the cafe in the train station, Isabelle ordered a glass of wine, and the woman behind the counter carded her, staring skeptically at the ID even though Isabelle in no way believed she looked younger than twenty one. She was closing in on thirty, a number that meant nothing to her but was often spoken by the men in the office in the hushed whisper worried of conjuring the boogieman.

“Turning 30’s tough on women,” Terry told her. She made sure he noticed that she was staring at the deep lines time had carved into his forehead. “I’m not saying I agree with that. I’m just…” He trailed off, flinching away from her self consciously. Oftentimes their conversations ended like that.

Isabelle extended her hand to retrieve the ID from the woman at the cafe. “Look, if you don’t think that’s me then I don’t need the glass of wine.” Isabelle tousled her short black hair. “ It’s an old picture. I cut all my hair off a few years ago.”

Throughout the entire transaction, the woman didn’t smile once. By the time she was handing Isabelle her glass of wine, Isabelle had stopped smiling herself. She didn’t always intend to do that, mirror someone else’s reaction. Sometimes it happened as a defense mechanism, a means of survival in the world or an industry. Her earlier years working in broadcast and journalism had seen a more bright eyed, shamelessly enthused Isabelle. Edges had started wearing through the flesh of her daily grind, glacial but evident. When she started mimicking the dead pan ca dance and suspicious, skeptical stare with which she was so often greeted, the first of the edges broke the skin from the inside reaching out.

Isabelle ran her finger around the rim of the wine glass. She wasn’t sure she wanted it anymore. There were water spots around the stem and base, the imprint of the woman’s fingers where she plucked it off the shelf. An announcement in the station let her know her train had arrived at track two so Isabelle got up without even taking a sip of the wine. She could feel the woman’s head turning to follow her, undoubtedly wondering why the hell a full glass of wine was being abandoned on the table.

Not too many people were heading from Denver to Albuquerque that afternoon but there was a steady stream of them moving in an awkwardly synchronized shuffle, funneling tighter as the amorphous blob henceforth known as the passengers went from being scattered across benches to driven towards one singular goal. Isabelle was often exhilarated in crowds; she was impressed by what coordinated human energy could do. Even spontaneously coordinated energy like mob mentality, riots were fascinating to her. The idea of everyone being latched onto the same wavelength and riding it to its inevitable conclusion sounded a bit like magic to her, the kind of magic old women referenced when they discussed love and god.

Isabelle was drawn to the fantastical side of life though she'd learned not to mention it to anyone she didn’t know very well. Fortunately, she had the sharp instincts to never bring it up around the people she worked with, especially the men. She overheard jokes about a dizzy but sweet natured secretary who read everyone their horoscope and warned the office when Mercury was heading into retrograde. Isabelle watched the men exchange smarmy, patronizing glances with each other as the secretary folded the day’s paper over, searching for whatever sign one of them had deigned to give her.

“Can you imagine actually believing this shit?” Terry whispered to her once as the secretary performed an earnest reading of a concerning daily prediction. “How could Mercury doing anything have an effect on me?”

“People believe way stranger stuff than that,” Isabelle answered but she didn’t elaborate. Her response had been cagey enough that Terry clearly thought she was just trying not to shit-talk the only other woman in the office. Isabelle wasn’t about to admit that she had spent her life looking in creaking houses for ghosts and staring up at the night sky, pondering the hubris of her species to dismiss what they couldn’t fully understand. She didn’t believe in every little thing, every tale short or tale that was told to her, but she hated the notion that adults had to lose their wonder, their desire for magic and the inexplicable.

The jostling crowd was narrowing to a mildly single file line. Some people were knocking around in groups of twos and threes. Most were falling into place organically except for an older man who seemed to be keeping pace with Isabelle. She refused to look in his direction as she realized he was walking alongside her as if they were a couple. This wasn’t the first time a man glued himself to her side with the intent of getting her attention, and she wasn’t about to start a ten hour train ride fending off advances.

She extended her ticket to the conductor, and the conductor looked to the man next to her as if they were a couple. Isabelle shook her head. “No, just me.”

“The young lady won’t even make eye contact with me,” the man said, gravel voiced and warm. It burned in Isabelle’s ears the way brown liquor burned down her throat. That ‘hurt so good’ kind of burn.

Isabelle pointed to her ticket. The conductor seemed to be hypnotized by the situation, staring at the unlinked pair. He handed the ticket back to her, and Isabelle had already hurried past him, up the small gridded steps. She found her seat in the penultimate car across from a young family with two kids.

One of the kids was a small girl, maybe four years old. She was sitting on the aisle seat as Isabelle put her equipment in the basket overhead and threw her duffle bag on the seat. When Isablle looked in her direction, the little girl smiled.

“We’re going to the dessert,” the little girl told her, matter of fact and completely sure of herself.

“The desert, baby,” the mother corrected, giving Isabelle the universal smile of a parent promising their child wasn’t going to be talking to her the entire ride. “You want some snacks before the train starts moving? Don’t bother the lady. Have some snacks.”

“I’m not eating any snacks because I want to save it all up for the dessert,” the little girl declared, shooting her arms above her head, childishly spastic. Powered by excitement and a sense of rightness, the belief that something the adults couldn’t imagine was actually real.

Isabelle turned her attention out the window as the whistle blew overhead, and the clumsy single file snake of passengers was absorbed into the train. Denver sat slightly below them in the distance, as cluttered as Isabelle remembered it. She closed her eyes, and the train trembled forward to the desert, to the land of space and emptiness and the horizon.

Chapter 2: Cormac

Word Count: 1,786

Cormac shielded his eyes from the surrendering sun as he dropped his tools to the ground at his feet. The fence on the far end of the property had been busted through, and the sections around the broken piece were starting to sag as they held up the weight of their snapped link. Of course it would be the west end fence, he thought as he used both hands to shade his eyes. Of course I’d be starin’ directly into this sunset while I worked.

Had there been another person with him at the moment, Cormac still wouldn’t have bothered to say any of that out loud. He’d expect whomever was with him to ascertain from his narrowed eyes and lifted arm posture that Cormac wasn’t thrilled to be fixing a fence facing the branding glow of the desert sunset.

They weren’t sure who or what broke the fence. Tara, the old woman who lived with him and took care of the house, was worried there were more aggressive animals lately coming down from the mountains than the two of them were used to. She checked on the goats and chickens constantly.

“Coyotes never sleep,” she told him when she heard a screeching noise coming from the chicken pen in the bruise colored, star splatter panorama of early New Mexican morning. “Three a.m. means nothing to them.”

She had gone running out naked, shifting artfully as she pierced through the chilled darkness. Cormac had been asleep until he heard the howl of his own kind, the whistle of a noise that came from a place in between two worlds. He had heard it all his life; he had heard coyotes and wolves and plenty of animals that threw their faces heavenward and released into the sky. Not once did he confuse the two sounds.

Tara was faster to action than Cormac was. A product of getting older was what she always told him. Cormac was pretty sure it was just that they responded to things differently but Tara was insistent on this fact.

“I was calmer when I was younger,” she explained. “I was never sure of myself and my own senses. That ‘appens when you grow up a freak.”

She’d wait for Cormac to argue with her, either about her quickness to action or the fact that she referred to herself as a freak. The few times they had ever gotten into a fight, Cormac had drunkenly snapped at her for calling any of them that word. He hurled a glass of beer towards the wall, watching the foam do its vertical walk from suds to liquid to mess on the floor before he said anything.

“We’re not freaks, Tara.”

“We should be so lucky to be freaks. Ya want ta be ‘uman?” Tara’s speech had a hint of a Spanish accent in it, and she rarely said an H where there was supposed to be one. “I like being a freak, Cormac. Better than being one of them.”

For someone who didn’t speak much, Cormac put a lot of stock in words. He stoically corrected people when they accidentally called his ranch a farm; repeated the word ‘cowboy’ to tourists looking for a bull rider. There was a lot in these tiny, invisible things called words, a lot of power people weren’t quick to admit to. He thought it a funny flippant side of modern culture that words were becoming less important yet somewhat more powerful. Words were weaponized and wielded too cavalierly for anyone’s good. Cormac was acutely aware of this so he didn’t want him and his kind referred to as anything resembling freaks.

Maybe it was because Tara talked a lot that she didn’t think anything was as big a deal as Cormac did. “Principles, real strong principles like that are for the young,” she said. “Me? Now all I care about is what I can do right in front of me. The chickens, I can save. This ‘ouse, I can take care of. What people out there think about and fight about...what do I know of out there? It does me no good to get mixed up with all that.”

Cormac knew some of that was just hand waving. The Tara he had known for the past decade was someone who believed in the intangible and ephemeral; someone who experienced deja vu and spoke of energy. It was impossible, or so Cormac thought to himself, for her to not grasp the full spectrum of calling herself a freak. What the language was doing to her, to other shifters around her. Cormac winced at the word. As much as Cormac could wince.

The sunset was making it nearly impossible for Cormac to fix the fence. If he stood with his back to the horizon, the shadow of his broad shouldered body swamped the area in twilight purples. Facing the sun, he had to squint his eyes down to slits, and the sun still blinded him.

“Well, damn this all to hell,” he muttered, dropping to his knee and tilting his cowboy hat as far forward as he could. He was faintly relieved to hear Tara calling him to come up to the house. He gathered his tools, and left the job unfinished, hoping he’d have time to return to it the next day.

“I knew there were coyotes!” Tara was saying as Cormac approached the house. She was standing on the porch, a bloodied chicken carcass draping from her hands like a wilted trophy. “I didn’t see this one in the morning when I checked for eggs. The coyotes must be ‘unting in the daylight.” She scanned the wide open plain, nothing but red dust and distant rock formations. “Or maybe it was rabid.”

“You found it in the coop?”

“Just now.”

Cormac nodded. “Alright.”

Inside the coop was dark and stuffy, a sweaty sawdust smell of animal production. Chickens clucked and walked past him as if they were completely unaware of his presence. Cormac was amused at how easy it must be for a predator, be it coyote or otherwise, to kill a chicken. He had seen goats fight back, knocking over humans and headbutting frisky dogs, but chickens were babes in the woods. One of them stared up at him with blank, beady eyes then moved her head forward and backward in a motion so smooth and discrete that she looked animatronic.

Towards the back of the coop were signs of a struggle. Dark blood in splashy designs stained clumps of hay. Everything was sticking together, dank and musty, roiling thick air that tasted like the salt of a mammal’s body. Cormac lowered himself to the floor and brought his nose as close to the clustered blood and hay as he could without touching it. He inhaled deeply, an acrid scent like old urea spiking through his nostrils. This was a smell he had never encountered before, a predator with which he was completely unfamiliar. He inhaled again, and got a heady rush he couldn’t explain. It was like seeing someone in a dream but not recognizing their face. Something in that scent triggered a memory for him but damned if he knew what it was.

He exited the chicken coop, flinching as the curtain call of the sun struck him directly in the eyes. Tara was waiting for him, dead bird still in hand. “Was it a coyote?”

“Don’t think so.”

“Maybe mountain lions. Something we’re not used to seeing.”

“Just a guess but mountain lions probably would do more than rip apart one chicken.”

“I ‘aven’t counted them. Maybe more were taken.”

Cormac almost shook his head then he almost shrugged. He decided on doing nothing. It didn’t make any sense to him to act like he knew anymore than she did at that point.

“Give me the dead one,” he said, extending his hand towards Tara. “Maybe I can get more of that scent.”

“You picked something up?”

“Sorta.”

The weight of the carcass was surprising to him. It always was. When he picked up a living bird, full of peculiar noises and sharp, jittery ticks, they never felt as heavy as they did when they were dead. It was like the animation held them just slightly aloft, and when that mechanism was interrupted, they were glued to the ground. Gravity affected them more strongly, more mercilessly. Cormac also knew that this fact applied to humans and shifters as well. Once it was over, they were all on the same level as chickens.

That scent, that unplacable but eerily familiar scent, drenched the chicken carcass. Cormac inhaled until he thought he was going to bust open, delirious and drunk from the strange smell. It triggered the hunt in him, and he loved the hunt. Tracking through the woods in the mountains, sniffing the air as it burned his lungs. He didn’t get to hunt as much as he wanted to plus he and Tara had made the promise never to attack animals that belonged to anyone. It didn’t matter that their closest neighbors were ten miles away; Tara and Cormac wanted to keep the peace, not tear through their livelihood.

“I can’t get a hold on this scent,” he told Tara as he breathed in the open air, trying to find its molecules dancing in the wind. That was how smell traveled in the desert: on the waves of a sirocco, a dervish of hints and particles.

“Are you going to track the coyote?” Tara asked as Cormac handed her the chicken and started walking towards the open plain, a rock formation in the distance sending the tip of a long shadow like a finger pointing towards the ranch.

“I’m going to try.”

“Cormac.” She waited until he turned back to look at her. “Don’t shift in the open, alright? Find a ‘idden spot for it.”

“You shift running into the chicken coop.”

“That was nighttime, and I’m so old. Nobody’s eyes even see me no more.”

Cormac just nodded in reluctant agreement. There was no sense in arguing since he hadn’t planned to shift where anyone could see him. The ranch was pretty isolated but there were always campers to worry about or dirty, sore-covered vagabond types that were being burned alive in their skin by the sun and had nowhere else to go. At least with the likes of them, nobody would listen if they came shambling into a town and spoke of men transforming into wolves, tearing through the crimson desert of all fours.